Myron Thompson Dusinbury (1838 - 1921) was an early resident of Oakland. He worked on the San Francisco and Oakland Railroad and at the Oakland Bank of Savings. He was married to Frances D. Dusinbury, (Plummer) and father to James P., Harry Edward, John Benjamin and Mary Webster Dusinbury.1

OAKLAND PIONEER RAIL MAN DIES2

Myron T. Dusinbury, among the oldest ranking members of the Society of Oakland Pioneers and conductor of the first steam railroad in this city, died yesterday at his home, 1504 Adeline street. He was 83 years old.

In 1861, Dusinbury came to Oakand, where he engaged in laying tracks for the steam railroad on Seventh street between the Point and Broadway. When the work was completed he was given the job of conductor on the same train of which James Batchelder was the first engineer. In 1870 Dusinbury left the railroad to become assistant cashier of the Oakland Bank of Savings, located at Broadway and Ninth street, and of which P. S, Wilcox was then president. He held this position until his retirement some years ago.

Dusinbury was born in Brunswick, New York. He is survived by a widow, Mrs. Frances Dusinbury, and three sons, Harry E., John B. and Marshall Dusinbury. Dusinbury was a member of Oakland Lodge No. 188, F. and A. M.

Man Who Built Railroad from Oakland To New York Recalls Early Day Events3

Myron T. Dusinbury, 82, Was First Conductor on the Old Seventh Street Line.

MYRON T. DUSINBURY, Oakland pioneer, who helped build

MYRON T. DUSINBURY, Oakland pioneer, who helped build

first railroad out of Oakland, and who recalls time when this city was a forest of oak trees.

"What are you doing here, young man?"

"Building a railroad." "A railroad! To where?" "New York."

The conversation was engaged in down on Seventh street, back in '63. The questions were directed by a stranger to Myron T. Dusinbury, a workman on the Seventh street line that was building through to the foot of what is now Thirteenth avenue.

The assurance that the line was to run through to New York was purely facetious, but some time later the first Pullman train came in from the east over that same Seventh street road.

Dusinbury, now approaching his eighty-second year, remained on the construction job until it was finished and was its only conductor for six years. There was one engine in the equipment, and one train. All the commuters went to San Francisco over the line and whenever any one wanted to know where any one else was they asked Dusinbury, He knew whether they were in town or not.

HE IS GREAT-GRANDFATHER

The pioneer now lives at 1504 Adeline, where he has resided since 1870, his house having been designed by Dr. Frank Merritt. He has raised three boys and one girl of his own, besides two grandchildren. He is now a great grandfather.

The house stands opposite the De Fremery Park, the dense growth of oaks on which is a reminder of what Oakland used to be, and why it is named Oakland. The growth of oaks is said to have been similarly dense all over the place, though it is hard to believe.

Dusinbury had some eight acres of land in the old home place, and tells how when a young man the late Judge Frank B. Ogden used to shoot quail and squirrel there.

The forests of oaks used to attract the people of San Francisco over to this side for picnics and the road did a great business on Sundays. The picnickers paid 50 cents fare across, which information indicates that in respect to fares the charge is merely reverting to the status quo.

The parties used to detrain at a point between Adeline and Market, where the trestle was 15 feet high, and go toward the estuary to Hardy's woods, a place where the growth was more dense than ordinarily. Every Sunday brought the week-enders to this side in boat and train loads.

MANY LIVES LOST

One such party was boarding the ferry for the return trip in 1868 when the apron gave way, precipitating them into the water. Many were lost. Dusinbury ran the train back to the end of the line and sent a boy on horseback to Alameda, where the then owner of the road, A. D. Cohn, resided. [I believe the name is misspelled, I think the author means Alfred A. Cohen. - MF] He still has the note he sent to Cohn. It says:

"Side gangway gave out at wharf. Passengers overboard. Some are missing. Don't know how many."

Cohn went to the scene with a horse and buggy.

In those old times when the passengers alighted from the train at Broadway they went down the street toward the estuary. All the town was down there, but it wasn't much of a town at that. No one thought it was going to grow all over the oak flat, as it has done.

Dusinbury remembers the earthquake of 1868. He was running the train toward the pier when there was a terrific shakeup. He stopped and got out to investigate, thinking it had been derailed rounding the curve that avoided the Badgers property. The curve had been made necessary because Captain Badger had stood guard with a shotgun and refused to let them go through.

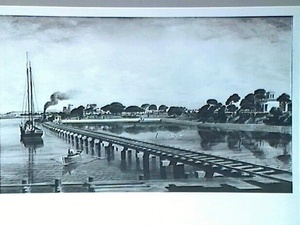

Residence of Capt. Thomas W. Badger, Brooklyn, from the south, painting, c. 1871, Oakland Museum of California

Residence of Capt. Thomas W. Badger, Brooklyn, from the south, painting, c. 1871, Oakland Museum of California

CHIMNEYS FALL

The wheels were on the rails all right and it was quite a time before they could figure it out, not until they saw the chimneys of the nearby houses lying flat,

The road was originally built on piling all the way from Oak street in some places to a height of fifteen feet or more. There was at that time no solid surface in the entire distance. How the area has been built up with solid ground is a lost story, so gradual has been the process that it has escaped notice. There was no Bret Harte here to record the time when the water game up town, as he did in San Francisco.

At the time the Seventh street line was built there was only a short stretch of track on Market Street and a line running from Sacramento to what was known as Shingle Mills. A man named James Larue owned two boats on the San Antone - Oakland run. Goss and Stevens, the builders of the Seventh street line, told Dusinbury to offer Larue $100,000 for his boats. Larue accepted and the entire Eastbay transportation system came into one ownership. The Southern Pacific came along later and acquired it. At first the latter road came into Vallejo and ferried to San Francisco. Dusinbury says the engine of one of the two boats acquired at that time is still doing duty in one of the ferryboats.

FREE ROAD TROUBLES,

There was a long period when the Seventh street line was a free road, so far as way fares were concerned, within the city limits. The charter by some twist prevented the collection of fares between stations. The fare was trivial, only 10 cents between any two stations. The company tried to collect it in spite of the charter, and Dusinbury says it was the source of his chief trouble. If the passenger got too sassy he was put off, but if he merely sat down, occupying the seat of a real pay passenger, he was allowed to ride to his destination. The situation continued for several years, and in order to keep the dead heads off, the company put on gates.

The high prices prevailed on the line and across the bay until our own John L. Davie, then mayor, put a crink in them by establishing the Creek route.

After leaving the railroad service Dusinbury went into the Oakland Bank of Savings, and for many years, until his retirement, was identified with the financial history of the, [sic] which is another story within itself.

GIVEN TESTIMONIAL.

Among the pioneer's most valued souvenirs is a testimonial given him on the occasion of his marriage away back in the sixties. The testimonial was signed by eighty of the most prominent people of Oakland as its population was then constituted. The names include many of the best known of Oakland's history. The testimonial reads as follows:

"Oakland, April 15, 1868.

"Myron T. Dusinbury,

"Dear Sir: It is a trite says that a man deserves no special thanks for performing his duty. But when a man in a position like yours performs his duties cheerfully and uniformly finds pleasure in exerting himself to make travelers comfortable, it manifests a goodness of heart which deserves, and generally commands, the respect and esteem of those who have witnessed his exertions, as well as those who have been the recipients of his attentions. Thus, as conductor on the San Francisco and Oakland Railroad Company, you have fairly won our respect and esteem, and we are glad that the occasion of your marriage affords us a fitting opportunity to present you with a token of our personal regard in the form of the accompanying case of table silver and a table castor - all of which we beg you to accept with our warmest congratulations to Mrs. Dusinbury and yourself, and our hearty wish that your highest anticipations of happiness may be more than realized in your married life."

The testimonial is signed by the following:

E. Bigelow, H. C. Lee, Thomas Anderson, H. S Hudson, D. Ghirardelli, L. Huff, A. S. Hurlburt, H. E. Matthews, E. P. Sanford, W. H. Miller, Charles D. Haven, E. E. Sessions, T. Bugge, George C. Potter, Thomas Newcomb. F. Reichling, George Tait, Dr. H. E. Knox, R. S. T. Wills, T. B. Bigelow, A. Cummings, C. Brown, M. D. Townsend, William Gagaw, E. McLean, Rev. B. T. Martin, G. Tonchard, James Stratton, John Bray, H. A. Mayhew, Captain E. Hackett, J. F. Stein, J. Williams, S. H. Wade, Charles Vincent, J. B. Scotchler, W. K. Flint, Captain Travers, Charles Packard, J. A. Maganos, Captain Badger, Captain Brown, H. D. Bacon, W. S. Blunt, Alfred Rising, C. W. Howard, G. F. Walter. J. C. Sanborn, W. C. Tompkins, C. F. Wood, William Surryhn, G. H. Moore, Edwin Harris, J. Cullen, H. Barroilhet, J. B. Watson, P. Bartlett, 0. Bell, R. W. Heath, Captain Wilcox, J. S. Emery, Hiram Tubbs, C. W. Kellogg, Rodman Gibbons, Samuel Merritt, J. M. Moss, R. W. Kirkham, R, H. Ennett, F. G. Burke, G. F. Smith, John Wedderspoon, James Gamble, G. W. Armes, A. Cannon, E. G. Matthews, J. W. Dwinelle.

TRANSPORTATION.4

A Spirited Contrast Between the Then and the Now.

M. T. Dusinbury's Merry Tales of Early Railroading. Some Prominent Men In Unusual Roles and Queer Situations.

The "local" is, in 1891, a bustling twelve-section element in the busy life in Oakland, governed by iron-bound time-tables, kept garnished by a little army of uniformed attendants rushing as though the sole object were to decimate the population.

At the time of which I write it was a romantic, go-as-you-please, steam coach sauntering along through the forest, subject only to the personal convenience of the conductor. I was the conductor.

However, the good old sawed-off engine with caboose attachment, was run solely for business, and the passengers bad to pony out their dimes, too, but the local of today giving thousands of beardless dudes free rides and an excuse to parade their empty purses and emptier heads - well, it makes me smile.

But I am beginning at the wrong end of my story.

In August, 1862, two young men landed from the steamer Contra Costa at the foot of Broadway. They carried all their worldly goods with them, but as these consisted solely of a blanket, pick and a shovel, they did not prove much of an encumbrance. Being strangers they knew not whether to go to the right or to the left, so they struck out into the forest and emerged from it near Oakland Point.

Although it was easy enough for a man to lose himself in those days, it was hardly possible that he could ever make a wrong call at a house, that is, if be were in the same tract, because the whole country west of where Market Street is now, only boasted of six or seven houses, and the least distance between any two most have been a little less than three miles.

Let me call them to mind. I know them all, oh, so well! I need to look at them a few years later and wonder how many centuries would pass away before the district would offer me sufficient inducement to stop my train. However, the inducement came sooner than I expected, and it was of the gentle persuasion - but I am going along too fast.

There was Mr. Havens' house, and on the other side of the mud pond was Coyote Smith's. G. G. Briggs lived just below Adeline street and Dr. Edward Gibbons and Theodore Bagge where Center street now is. I almost forgot to mention the dairy kept by one Graffelman where the railroad yards are located now. This is a complete directory of West Oakland, when the two solitary wights just referred to came here to seek their fortunes.

One of them is at present a druggist in San Francisco; the other is your humble servant

Down on the beach there stood an old shanty that had been built some years before by Rod Gibbons. At the same time be built the house he drove a few piles in the mud by way of a starter for the water front. This very limited wharf went for years by the name of "Gibbons' Folly," but as the present depot includes the very spot were he drove his piles, Gibbons wasn't such a darn fool alter all - he was merely ahead of his time.

So much for the first wharf in Oakland. Now for our shanty. After we were engaged by Goss & Stevens to work on the prospectíve Oakland Ferry and Railroad Company we were allowed the use of this little house, but as all the windows and doors had been shot away by duck hunters, the contractors sent down "Colonel" John Scott to replace them. Scott was afterwards editor of the Oakland Transcript. Once or twice after we took up our quarters in it the hunters used to shoot through the windows, but the news that the population at the Point was increased by two was soon, however, all over the city and we ceased to be awakened in the early morn by duckshot falling on our faces, after they had gone through the window and struck the opposite wall.

We were told to stay at the Point and commence to build a railroad through the city - just the two of us. The other fellow was the boss; that is to say, he kept the time (I had no watch) of himself and the gang. I was the gang, and he did not sit up nights to keep his account straight, as we worked by the month.

Of course the object of our being there was merely to hold the franchise, and turn over a few shovelsful each day as an excuse for being there at all. That's all we did, except to cook and eat.

People used to drive down to the works and ask all manner of questions as to when we would have the first train ready to start. We always replied that we were building a railroad to run across the continent, but, in the absence of a single tie or rail, it was hard to make them believe it.

Well, we continued building our continental railroad for several months - at least we ate, cooked, smoked and turned the regulation sod every morning; and what was more important than all, we held the franchise. We might have done more work had our house been on wheels, so that it could have been moved and kept abreast of the track as we leveled it. As it was, we did not care to go too far from home in case it should come on to rain.

After leveling fully one hundred feet of the road in six months, a gang of men was brought down from The Dalles, Or., and work commenced in earnest.

That knocked my foreman out. He was all right so long as he was boss of such a gentle gang as myself, but he could not stand being a common laborer.

I wasn't so independent.

In September, 1863, we finished the road to Broadway. I was appointed conductor, and we began to run about six trips a day. There was just the one train, consisting of an old engine from the Market street road, San Francisco, and four cars. The locomotive was just like a threshing machine engine put into the end of a box car, but she was about a stand-off for the steamer, the Louise, which connected the end of the road with San Francisco.

"Old Betsy" (that's what we used to call the engine) was subject to some very strange irregularities. She got tired, occasionally, and wouldn't pull. Sometimes we started from the wharf with all the rolling stock owned by the company - to wit, "Betsy" and four cars - and landed at Broadway with nothing but the engine and caboose. This is how that happened: When we got half-way on our trip the train would suddenly stop, in spite of the fact that the valves were open and brakes loose. I would ride the bell as a signal to start up, with no result. So I'd uncouple the last car. If that did not help, I would detach the next one. If after going a bit further "Betsy" stopped again, we would put all the passengers in the caboose and let the engine go with nothing else to pull. There never was a time when she refused to go alone. Alter repairing damages we would back down and gather together the scattered fragments of the train.

After this the company built another engine. She was much better and larger than Betsy, in fact she was so large that they could not get her alI into a box car, so they let one end stick out.

The people were all good-natured in those days, and thought anything better that being stuck on the bar for twelve hours, as they were likely to be if they took the creek route and landed at the foot of Broadway.

Ned Hackett was captain of the steamer Louise, and his brother John was mate. John, however, used to do the greater part of the navigating of the sbip, and the captain used to navigate the ladies around the deck.

We ran to Broadway for several months before the road was finished to East Oakland, then called San Antonio.

There were no station agents, no switchmen and no telegraph operators in those days. All these services were included in the conductor. In spite of his importance, however, he did not think he owned the road and that the passengers were under an obligation to him. That kind of conductor developed later.

Of course we had to turn our own switch, and so, to save time, we made running switches. I used to jump off the car, throw over the lever and jump on again. The boys noticed this, and thought it would be an excellent way of testing my temper. On several occasions they covered the switch-lever with tar. It was only lately that I discovered who the guilty person was.

I was standing on Broadway a few months ago talking to a friend, when we were accosted by a gentleman whom my friend knew.

"Dusinbury," he said, "let me make you acquainted with Senator Frank Moffitt."

"My acquaintance with the Senator is as old as the railroad," I replied. "I helped to raise that boy."

"You did that," replied the Senator, "and in more ways than one. Many a time you raised me with your foot for stealing rides on the 'local' twenty-five years ago. However, Dusinbury, I got even with you, but you didn't know it."

"You never did," I said.

"No?'' said the Senator, smiling a wicked smile. "Did you ever find the lever of the switch covered with tar?"

"I should smile - and do you mean to say that -"

"I mean to say that I did it," said the Senator, laughing,

"Well, Senator, I frankly forgive you," said I generously, extending my hand, which the Senator wrung warmly.

(Senator Moffitt is a much bigger man than I am, but of course that did not influence me.)

All the boys got down on me for making them pay way fare between stations. I disliked it very much, but my orders were very strict and so I had no alternative.

One day I met A. A. Cohen, who was controller of the road, and told him what I thought of exacting fares. I told him I had conscientious scruples about the righteousness of doing so.

"Why shouldn't they be collected ?"' he asked.

"Because there is a clause in the franchise stipulating for free transportation within certain limits," I said.

Mr. Coben smiled. "Have you read all the clauses in the franchise?" he asked. "Yes, every one," I replied.

Cohen laughed more than before. "Did you notice another cause granting us the privilege of putting obnoxious passengers off the cars?"

"Yes, I did."

"Well, then, please do consider that every passenger who does not pay fare is obnoxious."

So the matter ended.

When the Central Pacific Company took charge of the road they considered this way-fare business too insignificant a matter to bother with, but things have changed since then. What was a little mole hill in those days has now become a stupendous mountain, to tunnel which has proved more than the genius and tact of a Huntington can accomplish,

I have watched with great interest the increase of traffic on the local, and am quite sure that if the railroad company had continued to collect the fares as I used to do there would be no more free traffic on Seventh street than on any other line. They are paying dearly now for that little expression of hauteur a quarter of a century ago.

After we had our line through to East Oakland we increased our service to ten trips a day. I think at this time one more car was added to the rolling stock. On Wednesdays and Saturdays we used to run an extra trip to accommodate those who wanted to go to the theaters in San Francisco. A monthly ticket in those days used to cost $7 50, but they did not entitle the holder to the theater trip.

Jim Bach [Batchelder - MF] was the engineer on the old "Betsy" all the time I was conductor, and indeed he only left the local service about six years ago. Jim always had an idea that he would like to make a trip around the world. Since he left the road he has gratified his desire, and is traveling somewhere abroad at the present time.

We never had but one collision on my train. You may think it strange to bear of a collision where there was only one train on the road. I was making the flying switch at East Oakland. I forgot to jump off and turn the lever, and so the cars followed in on the side track and knocked smithereens out of the caboose. I never wanted to be president of the road so badly in my life. I had my story all fixed to tell the old man, but the big earthquake of October, 1868, helped me out, as the collision occurred in the previous evening, and nothing more was ever said about it.

At the time of the earthquake I was on the train, abreast of Badger's Park. I felt the train rock heavily, and so did Jim, for he instantly stopped the engine. We examined all the wheels and were surprised to find them still on the rails, so we knew that there must have been an earthquake.

"What's the matter?" I shouted.

"Matter! Look at the chimneys," he said.

I did so and noticed that several of them had fallen down. When we recovered from our fright we started again, but when we arrived at the old drawbridge it was so twisted and shaken as to be impassable. We were in a pretty fix. We had the best engine with us and could not go any farther.

Jim and I made our way to the Point, brought old "Betsy" out of the stable and after a lot of oiling and coaxing we were able to run a light train of one car for a few days till the bridge was repaired.

During my six years on the road we only killed one person and injured another.

All the old residents will remember the engineer, Jim Batch, [Batchelder - MF] as a very careful man, and to his attention to duty the freedom from accidents is to be attributed. Everybody that used to patronize the "local" twenty years ago, used to know Ashby - "Old Ashby" everybody called him and I don't know his first name even now. [James T. Ashby - MF] Ashby used to run the newspaper Department for W. B. Hardy then, and was a man of considerable importance. There were no papers published here.

Old Ashby went across the bay on the first boat to bring the San Francisco papers here. The news was of so much importance in those days that the Superintendent gave me orders on no account to leave Broadway without Ashby on his trip. Ashby controlled the local in those days.

One Fourth of July the apron at the end of the wharf gave way and thirteen people lost their lives. I don't understand yet how it happened that I wasn't killed. The handle of the crank arrangement flew across my face with the speed of lightning and actually struck my goatee but did no further damage. By a strange coincidence I was also present at an accident at Melrose when thirteen people were killed, and also another at Webster-street bridge on Decoration Day of last year when thirteen lives were also lost.

One day, while collecting, I ran across a queer customer standing on the platform. I asked him for his fare and he said he had no money. I told him to get off. He did not wait till we got to the station, but off he went, end over end. He did not get on again for several days. I learned after wards that he was half-witted, so I took pity on him and let him ride. He used to help us with the freight.

On one occasion Brakeman Owen McLaughlin ard Jim Mullgover, the wharfinger, were arguing the point as to whether an idiot could get get drunk. McLaughlin said they could not, and Mullgover said no one but a fool would get drunk. Anyhow, they concluded to try it on poor Bob (that was the boy's name). They got a tin bucket of whisky that they didn't pay for, but which they obtained by tapping freight, aud Bob drank about a pint. They then put him in a box car to await developments, but the liquor never fazed him. We found out afterwards that it was Jerry Hanifin's whisky. Jerry was selling whisky in those days, and has been ever since, but even now I believe hasn't forgiven us for telling about our fun with Bob twenty-five years ago, and the lack of stimulus in his whisky.

On one occasion I was arrested for putting a man named Dan Smith off the cars. Dan used to run a little bake-shop in West Oakland, and one Sunday he and his wife wanted to ride gratis. It did not work though, and when the train stopped I threw him off.

My trial came off before Judge Shearer and I was acquitted. Although the judge had no direct interest in the road, I was sure of acquittal, because it was a test case as to my right to put obnoxious people off the train. The superintendent of the road, A. A. Cohen was my lawyer, but he was in reality defending himself. I don't know whether he and Judge Shearer were friends or not.

It is not generally known that Richard P. Hammond, the Police Commissioner who recently died, was for a short period previous to 1870, the superintendent of the local road; but he was, and used to bring young Dick over and let him ride on the engine for an outing.

After six years' service I decided to leave the road. I remember telling of my decision to H. D. Bacon, which caused him to make a very significant remark:

"Well, well," he said, "you are the very first conductor that was ever known to resign."

But things have become demoralized on the "local" since then. Instead of having to wait at Broadway for an hour or two wondering if the old caravan was ever coming, it takes a man all his time now, to get out of the way of the frequently-running trains.

In my day the conductor ran the company, and was in the confidence of the proprietor, but now a conductor is simply a call-boy in buttons, so far as the general public is concerned.

However, I suppose the new order of things is in harmony with the age, and is appreciated by the present generation. The six trips a day were even a more frequent service to the dwellers in the forest in 1863, than the fifteen-minute service is in 1891.

But this is a world of changes. Go ahead ! boys. The city of Oakland will be yours altogether in very few years from now. Much as my mind lingers over the memories of the good old times, I am forced to acknowledge that life is far more pleasant in our city of churches than it was in the city of oaks, in the days I used to throw obnoxious passengers off the "local."